This post on The Guardian’s science blog has drawn a fair amount on interest in “new media” science quarters.. It’s pretty funny, although it occurs to me that there are probably writers out there who are taking it as a template for future endeavors.

Tag: science

Taking the temperature of permafrost and archaeology

Today the Saturday Schoolyard talk was about warming permafrost. The speaker was Dr. Vladimir Romanovsky, head of the Permafrost Laboratory at the Geophysical Institute at UAF. He gave a really good talk, explaining what permafrost is (permanently frozen ground, basically), why it matters if it melts, and how permafrost researchers go about taking its temperature (with thermistor (temperature sensor) strings down boreholes, mostly). He then went on to show how permafrost temperatures had changed through time as the atmospheric temperature had changed.

After that, he moved to predictive modeling based on climatic models. Using even a fairly middle-of-the-road climate model, it doesn’t look too good for permafrost in Alaska by the end of the century. He also showed active layer (the soil layer at the top that freezes and thaws every year) modeling done on a similar basis some years ago, and pointed out that over the 10 years since the model was run it had been spot on in its predictions. The active layer is clearly going to be a lot deeper if the predictions hold.

This is not good news for Arctic archaeology. Compared to most of the rest of the world, where archaeologists are left to puzzle out what people were doing from a few stone tools, waste flakes and potsherds, we get really good organic preservation here, which makes it possible to look at questions that can’t be addressed elsewhere for lack of relevant data. The reason the preservation is so good is in large part permafrost, and permanently frozen sites. Last week, when Claire was here, we were getting a lot of well-preserved 1600-1700 year old marine invertebrates from the samples. They exist because the layer was frozen for most, if not all, of that time.

I’m been thinking a lot about site destruction, and how to determine which areas are at highest risk, in order to prioritize field efforts. Perhaps because coastal erosion is the big and immediate threat at Nuvuk (and all the other coastal sites I’ve worked at except for Ipuitak, where the immediate threat was the seawall being built to prevent coastal erosion), I’ve tended to focus on that, as well as eroding river banks for sites along rivers. The melting of exposed ice wedges, which then leads to collapse of the overlying ground is also something I’ve been concerned about. And these are major threats, which can tumble entire houses upside down on the beach for the waves to destroy.

I hadn’t thought much at all about the risks to Arctic archaeology from a significant deepening of the active layer, which will mean that artifacts and ecofacts (animal bones, insects, etc.) will freeze and thaw every year (which is hard on things to begin with, often causing rocks and bones to split) and while they are thawed, they will be decaying. Even now, really old sites don’t have much organic preservation. Even sites that are in no danger of eroding are threatened with the gradual invisible loss of a great deal of the information they now contain.

Obviously, if we are going to develop a “threat matrix” for Arctic archaeological sites, this has to be part of it. I talked to Vlad a bit after the talk, and he thought he had students who could be put to work on this problem, perhaps by combining what we know about site locations in Alaska (by no means a complete listing) and the existing models for permafrost change. He also said that one could do active layer modeling for a specific site with a year’s worth of soil and air temperatures, so that’s something we definitely need to get started on.

Some interesting papers so far

I’ve heard a number of interesting papers so far. A bunch of them were in a session on digital archaeozoology. I find this interesting in part because I live and work in a remote area with limited research resources on hand, although for the size of the place they are truly exceptional. A number of highlights from the session below:

1) A paper by Matt Law on zooarch on the Internet. He’d done a survey of on-line arch data archives. People often use them heavily, but so far are not good contributors. People still see on-line publication as less prestigious (which is a problem if they are working toward tenure), but most would still be willing to participate if the process were straightforward enough.

2) A paper by Isabelle Baly & others about a big national database (INPN) the French are building of data on plants and animals from archaeological sites. Much of the data they are including comes from salvage and compliance excavations, which often don’t get published. This is a huge amount of work to pull together (especially with the staff of three that they have!), but it lets people do analyses which they could never afford to do otherwise. It seems to be available through a public website, which will let students and members of the public see and use the data themselves, which is pretty cool.

3) A paper by Jill Weber and Evan Malone about a set (30+) of skeletons of equine hybrids between donkey and onager, which are currently a unique sample. These are thought to be the Syrian Royal Ass, the Kunga, which was actually the Animal of the Year in Syria a few years ago. The problem was how to be able to preserve & share these bones, and study them without damage to the originals. Answer–3D laser scanning & “printing” them. 3D printing actually makes a replica of the item, and is very cool technology. Depending on the budget, the replicas can be very good. The scanned models in the computer are actually even better for doing measurements on ( something we do a lot in zooarchaeology) than real bones in some cases.

4) A paper by Katherine Spielmann and Keith Kintigh on the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR). TDAR is a large-scale data archiving and integration tool, developed at Arizona State University. The impetus was that a lot of archaeologists there had data that they were interested in comparing, in order to look at things across a broader area than any of them had studied individually, but were stymied by differences in the way that their data was stored. They are trying to develop an integration tool and data warehouse. I haven’t tried it, but it seems interesting.

5) A paper by Matt Betts, and a number of others about the Virtual Zooarchaeology of the Arctic Project (VZAP) –very cool 3D models of Arctic (and subarctic, since ISU has been working in the Aleutians/Lower Alaska Peninsula area under Herb Maschner for years, and that’s what they see most of) fauna. The bones are accessed through a very neat visual database interface, which lets you look for bones by species or by skeletal element (part of the body), which is the most common way to find things when identifying unknown bones. Often you can see you have a femur (thighbone) for example, but aren’t sure what animal it’s from. The best physical comparative collections of bones actually have a set of femurs you can look at, rather than having to go to a bunch of skeletons and find the femur. I’ve used this one, and it’s handy. As more species get added, it will only become more useful.

Off to a conference of archaeozoologists

… or zooarchaeologists or faunal analysts (people who study animal remains from archaeological sites), in Paris. The trip over was a two-day affair, involving not one, but two red-eyes. We had a good tail wind, so the Salt Lake City flight was about an hour and a half shorter than expected, which made up for a late departure due to bad weather.

The conference is feeding us lunch every day, and it’s pretty impressive for a university cafeteria. One starter, one main course, one cheese, one desert and one drink. The folks I ate with didn’t see it, but there are rumors that wine was available. The coffee breaks have great pastries and fresh fruit.

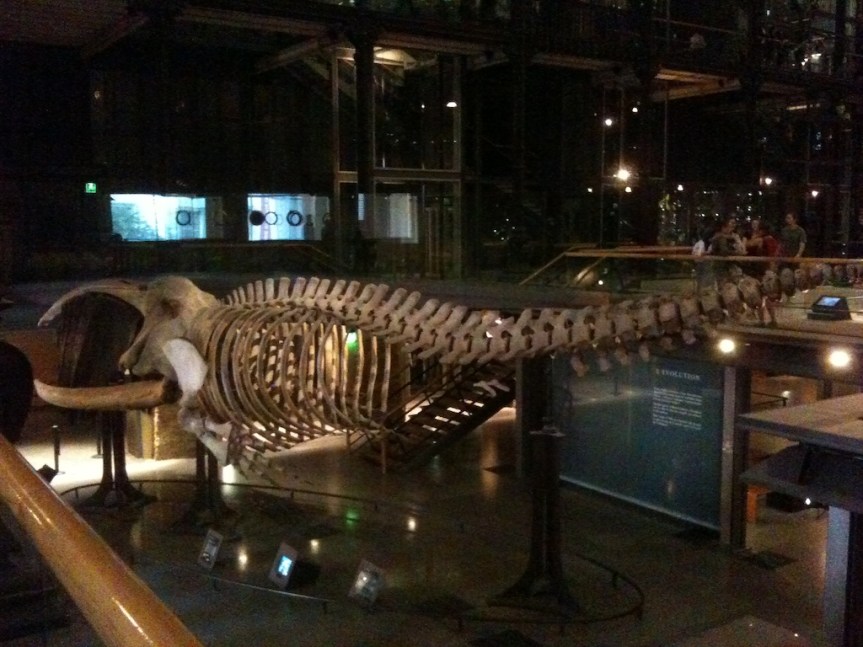

The opening reception was amazing, and they didn’t run out of food, frequent problem at such events. They held it in the Grande Galerie de l’Evolution (Great Hall of Evolution) of the National Museum of Natural History, which is just amazing. A few pictures from there follow. I took them with my phone, so the quality is not the best.

There are also some neat older mounts. The one of the tiger on the elephant is because a French duke was hunting on elephant back in India, and a tiger leaped onto his elephant. He was only saved because she was so heavy she broke the basket he was riding in. She was shot, and that’s the tiger in the mount, which he had made and donated. It didn’t say if it’s the same elephant.

Very neat website about Science and Barrow

Barrow is a pretty interesting place in terms of the sheer amount and variety of science that gets done here, as it has been since the 1st International Polar Year (IPY). It can be hard keeping track of it even if you live here and are a scientist. We don’t have a local newspaper reporter, and the radio station can no longer afford a full-time reporter, so there is no local source of science stories for the general public.

Many scientists want to let people know what they are doing, and what they are learning by it, but there are a number of barriers (another post for another day). One way is blogging. On bigger hard-science projects, websites and more are possible, since the cost of people to take care of them is really a tiny portion of the project budget.

A recent project called OASIS really takes this to another level. Dr. Paul Shepson, the PI, actually built in an author to write about the project, and things grew from there. Peter Lourie, the author, has written two children’s’ books and has moved on to multimedia. They’ve made a really neat website, which has video from a number of scientists who work in Barrow. There’s a lot from various folks on the OASIS project, but also from people who live in Barrow, like Fran Tate of Pepe’s, whaling captain Eugene Brower and even me. I actually got interviewed twice, because the sound on the first set got messed up, so I had to do it all over again when Peter came up again!

Definitely worth checking out.

A Cold Day at Nuvuk

It has been a busy week, with all sorts of things to do after the day’s fieldwork was over and the data was downloaded and backed up, including a public meeting (which will need to be rescheduled because the weather was nice and the TV didn’t get it on the announcement roll-around in time), baking dozens of cookies for the community potluck my employer was holding, and dealing with the aftermath of a minor ATV accident involving one of the students (she is fine, but wrenched an already sore shoulder and therefore will be on limited duty next week). We have tomorrow off, so I’ll provide more details and pictures on the fieldwork then.

Just a quick note while I try to get the flash card downloading. The pictures are all shot as hi-res JPEGs and RAW, so it takes forever. I doubt I can stay up long enough to post pictures tonight.

We worked today. Normally we do fieldwork Monday-Friday, because the students are paid by the hour (so they get practical job experience as well as archaeological training) and child labor laws make it complicated to work more than that, especially for the younger students. We had a vacation day on Monday, though, and since it’s a short season and some of the students are trying to earn money we decided to do a 5-day week anyway. In the end, only 5 of them made it to work today. One was out of town, Trina was taking part in a fundraiser for the basketball and volleyball teams, two were sick, one was hurt and we don’t know what happened to the other one. It was wicked cold this morning, so hats off to Rochelle, Trace, Nora, Warren and Victoria. Not only was it cold, it was windy & foggy (yes, at the same time). In fact, it was so foggy we were having trouble with the transit because the lens and/or the reflector kept getting obscured by water drops. And it rained before lunch, and toward the end of the day.

However, as compensation, we finished excavation of the first burial of the season. It turned out to have been disturbed, probably in the late 1880s, judging by the artifacts scattered along an old ground surface along with some of the individual’s bones. We found some very cool artifacts (a bit unusual for Nuvuk burial excavations) although they weren’t really in the burial. Highlights were a copper end-blade (for a harpoon head or possibly arrow), a split blue glass bead, and best of all, the cartridge for a shoulder gun. The last still seems to have a bit of black powder around the primer area, so we have it in VERY wet conditions, and I will try to clean it tomorrow before there is any chance of the powder drying at all. Our bear guard, Larry Aiken, who is a whaler, said it was the oldest style, shorter than the ones they use now.

As further compensation, we decided to order our lunches from the fundraiser, so Trina brought 13 lunches to the end of the road to Nuvuk (called my cell before she headed out), and Larry took a trailer back to get them. So we all had BBQ chicken, potato salad, rice, pancit and a hot dog for lunch, along with the hot beverage of our choice and chips courtesy of Nora! Even with the big propane cooker going the tent was cold enough to see our breath. We hung in and finished the burial, and tested the areas where two other single human bones had turned up in a trail. Neither one had a grave beneath it. We already have 3 other probable graves, based on subsurface indications in STPs, waiting for us next week.

So you want to do what to the tundra?

Heat it, it turn out. The Department of Energy has some experiments running in the lower 48 (that’s the Continental US for you non-Alaskans) which involve heating small patches of land to see what the effects of global warming might be. Better than just wait and see, no doubt, and it would give some guidance about adaptations that might work. Anyway, they are thinking of trying this on the North Slope. For the moment, they just want to test the proposed method in a very small area,less 30 m in diameter. (A meter is just over a yard, about 39 inches, for those who forgot about the metric system when they left school).

Barrow has many wonderful things, including the Barrow Environmental Observatory, which is 7466 acres of land set aside by the Ukpeagvik Inupiat Corporation, the Barrow village corporation (more about that some other time) for scientific research. It is actually zoned as a Scientific Research District by the North Slope Borough. That’s where DOE wants to test this. So, a plot had to be located. It needed to be near power and a trail. Craig Tweedie of UTEP, an ecologist, found a spot that seemed fit the bill, which had been disturbed in the past by tracked vehicles called “weasels” which NARL scientists used to use to get around on the tundra. Now everyone walks in the BEO when the snow is melted, unless matted trail is put down. The idea with a disturbed site was that it wasn’t much good for other research, so it’d work for testing the warming equipment.

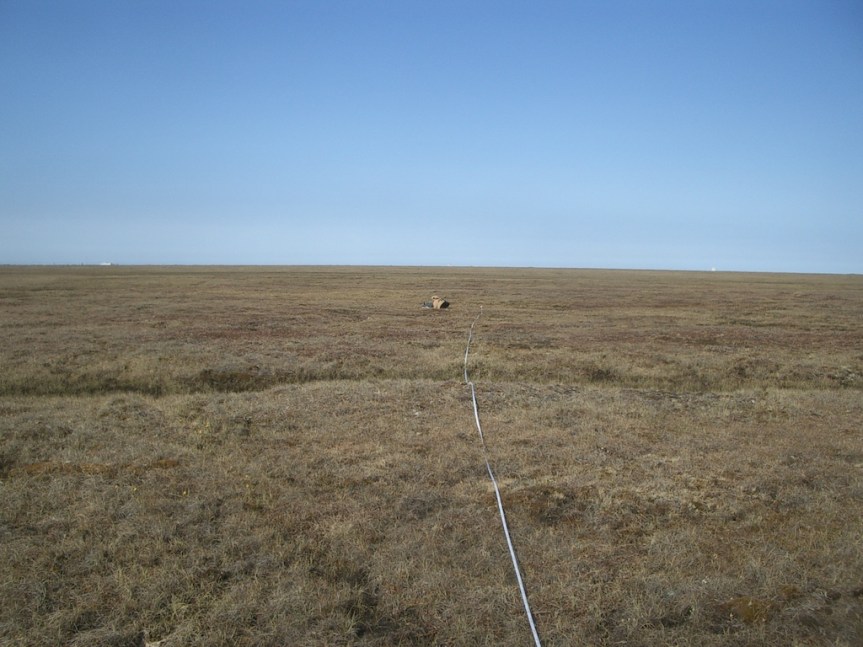

The next question is if there are any cultural resources (archaeological or otherwise) on the site. Since I work for the company that owns the land, that’s part of my job. Normally we’d wait until later in the summer when the ground is thawed more and the Nuvuk field season is over, but they’d like to try to install the equipment soon. So I went out this afternoon to look at the place for the first time and see what was what. There were a few pictures, but I guess archaeologists look at things differently.

I had a GPS location for the center point, so I programmed it in, got a 30 m tape and pin flags, and set off. First I drove to a pull-out on Cakeater Road, parked the truck, and took a half-mile or so hike into the BEO. There is boardwalk part of the way, and matted trail goes right past the site, although it isn’t very level, since the tundra it is built on is fairly lumpy and shifts a bit over time besides. However, it’s been such a late melt that a lot of parts of the trail were under water, so I had to do all this in Xtra-Tuffs & rain bibs. I’ve been coming down with something the last few days, so I really just wanted a nap, and wasn’t exactly looking forward to this little excursion. Luckily, the sun came out for what seems like the first time in days, and it was actually fun, although I took an amazingly long time to do it. Then I had to turn around and hike back to the road :-(. There were lots of birds around, and the buttercups and willows were in full bloom, so all in all a good day.

Once I got there, I put some chaining pins into the center point, and ran out a circle around it with a 25 m radius. The actual equipment is going to be a hexagon with about a 25 m max dimension, so this gives room for construction and a little wiggle room. I walked the whole thing in really close transects, much to the annoyance (verging on hysteria) of a shorebird which must have a nest nearby. Based on this inspection, it looks good for the tundra warming experiment. The only evidence of human activity on the site was the aforementioned weasel tracks, a crushed 55-gallon drum, and a flattened tin which probably held Blazo once. The area was pretty damp, and there was higher, drier ground nearby, so it’s unlikely to have any significant pre-NARL activity when we test.

Pizza & baklava, and so to bed.