My post on the Anagi crew’s whale has gotten a number of comments from people who are interested, one way or another, in whales. Some of them are genuinely interested in learning more about whales & Iñupiat whaling; others appear not to be. I’m going to try to answer some of the questions, and provide links to sites that can give even more information.

But first, see this Public Service Announcement.

OK, now a bit of history. Alaska Natives (and in fact many other Native Americans and Canadian First Nations people) have been whaling for 2000 years or more, since before the Thule culture developed, based on archaeology. Aboriginal whaling did not damage the whale stocks in any way that can be detected. What damaged whale stocks was European (and later Euro-American) commercial whaling. The bowhead was popular with commercial whalers because it was non-agressive and had a lot of blubber for whale oil, plus long baleen. Most Eastern Arctic stocks were decimated by the early 19th century.

In the western North American Arctic, commercial whaler Thomas Welcome Roys first cruised north of the Bering Strait in 1848, starting a rush to catch the plentiful and naive Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock of bowheads on which so many coastal Alaska natives and their inland trading partners depended. The whales soon became skittish and scarce and many Alaska Natives died of starvation.

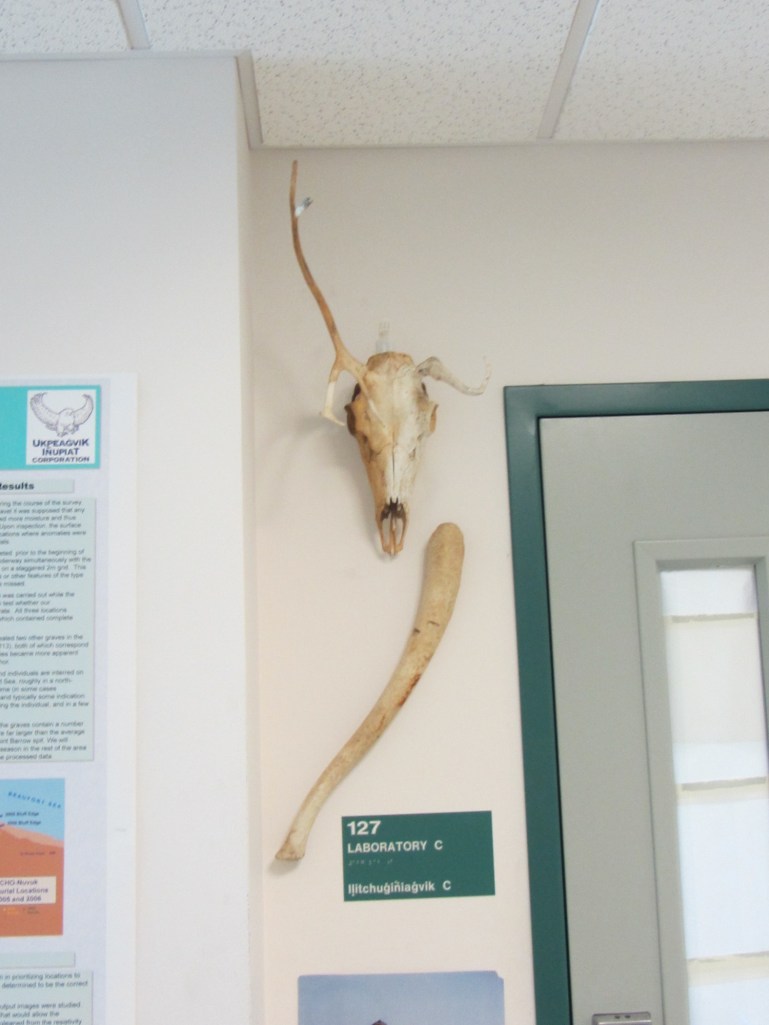

Once oil was struck in Pennsylvania, one of the big reasons for hunting whales diminished. But the baleen, the plates in a whale’s mouth that they use to filter-feed, was still valuable for buggy whips and corset and collar stays. Bowheads have by far the longest baleen of any whale (15 feet or more from a big whale), so they were still hunted until those items were no longer in fashion or needed.

Many coastal Alaska Natives had become involved in commercial whaling, including shore-based commercial whaling carried out with traditional Iñupiat techniques with Yankee style harpoons, to support their families. After commercial whaling ended, coastal whaling communities continued these hunts, combining traditional techniques and traditional and modern technology.

In the late 1970’s, some Western biologists, who were not experienced in the Arctic and knew little about bowhead whales (biologists didn’t back then) tried to count bowheads. They believed that the whales were scared of ice! They thought the bowheads had to travel in a lead and would come up to breathe in the lead so they could be counted. Even if that were true, they didn’t account for the fact that there are multiple leads, and that the whales only have to breathe every so often and that wouldn’t necessarily be where the observation post was. They came up with a count of several hundred whales, and of course, sounded the alarm. A moratorium was declared on Alaska Native whaling in 1977 (years before the moratorium on commercial whaling, I might add).

Since many families got (and still do get today) a significant portion of their meat from whales, this was a huge problem. Although wages may look high in places like Alaska’s North Slope, costs are high too, and many families do not have someone who is working in the cash economy and can afford to feed a family on store food and whatever else they can hunt (and of course full-time work does interfere with hunting, which was traditionally a full-time occupation itself). Most Iñupiat had never heard of the International Whaling commission, and couldn’t understand why they felt it appropriate to starve human beings by forbidding them to feed themselves.

They were particularly puzzled because senior whaling captains and hunters who had spent many decades on the ice had observed that the bowhead population appeared to be growing from the depths it had sunk to by the end of commercial whaling. They knew that bowheads are not scared of ice. In fact they can breathe under quite thick ice (they become positively buoyant and use the bow on their head where their nostrils are to push up the ice, cracking enough to let air into the little tented space formed under the ice and breathe there, and then submerge and go on about their business), and that they would not restrict travel to the near shore lead, so they knew the count was wrong.

The North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management, with many cooperating researchers over the years, has been studying bowhead whales ever since. They soon developed a much better way to count them, which is continually refined. Counts now show an annual rate of increase of 3.2%, which is really high for such long-lived animals.

The Alaska Native Bowhead hunt is highly regulated. The Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC) manages the hunt under authority from the US government. There is a quota of strikes (not whales taken, but whales struck so there is an incentive to land every whale struck if humanly possible), which is established based on document subsistence needs of each whaling community, in light of the population estimates. This quota is set so that communities get what they need and no more. The harvest is considerably below what population biologists would consider a sustainable harvest if they were talking about elk, or caribou, or mule deer. As long as something else, like marine noise or a massive oil spill in Arctic waters, doesn’t come along and decimate the population the way commercial whaling did, this is absolutely a sustainable harvest, carried out by people who entire culture is centered around that harvest.

The AEWC divides the quota between communities, based on active crews and population, and approves the transfer of strikes between communities (if, say, the ice is bad in one place and they can’t catch whales, they may transfer their strikes to a place with better conditions) since the maktak and meat is shared and everyone on the North Slope and beyond benefits if whales are taken. Only captains and crews registered with the AEWC are allowed to take whales, and violations of rules, ceasefires, etc can and has led to punishment or suspension of the offending captain.

When a whale is taken there are traditional rules for sharing which vary by community. In general, specific shares go the captain, the boat (itself–although obviously the boat owner disposes of the boat’s share), the harpooner, the other crew members, and the other boats which helped tow the whale back to be cut up. Anyone who shows up to help with the butchering (even a little) gets a share. My daughter helped a very little once when she was about 8, and she came home with a small share. The captain’s wife and her helpers cook round the clock after the whale is ashore, and when they are ready, the captain’s flag is hoisted and anyone who wants can go and get fed (they will usually send to-go plates to house-bound Elders).

After that, the captain and crew get ready for a celebration where a great deal more of the whale is shared with whomever shows up. People get whale meat, maktak, kidney, intestine, tail, flipper, gums, plus goose soup, mikiaq (whale blubber, meat & blood, fermented–and before you say gross, when was the last time you ate curdled drained milk with mold on it–AKA a nice Stilton or Brie?), rolls, cakes, fruit, etc. Most families in the community go to at least one of these every year. Many go to all of them. The amount given to each person depends on how many in the family (and the servers pretty much know or the people sitting around do, so no one fibs). Captains also give out meat & maktak at Thanksgiving and Christmas feasts to whomever shows up (usually much of the community), and usually will provide some for potluck and other festivities as well. They also share with Elders & folks who need it during the year. Most of the folks with whom it is shared share it farther. Shares travel to Anchorage and even to the Lower 48. Some of the people who get shares send back things like berries or smoked salmon from their area, or caribou from the interior.

None of the whale, or any other marine mammal for that matter, can be sold, with the exception that Alaska coastal Natives can use baleen or bone or ivory to make handicrafts, which they then may sell. They are not allowed to waste the rest of the animal just to get these products.

There is a great list of links to good solid information on the bowhead whale and bowhead hunt here.