The past couple of weeks have been really hectic. The local students have been working in the lab, and I’ve been dealing with logistics non-stop.

We’re at the point where we could go through the bags from the shovel test pits. In the early days of archaeology, only artifacts were collected, and sometimes only the unbroken ones, at that. The details of their provenience were often recorded in very broad term. As the discipline progressed, new methods kept developing, and it became clear that many of the things that had been discarded could have yielded information, had they only been collected. The pendulum swung toward keeping everything, including large volumes of samples, on the principle that someday methods would catch up, and then the information could be recovered. This is the same reason that practice moved toward only excavating part of a site, or even of a feature.

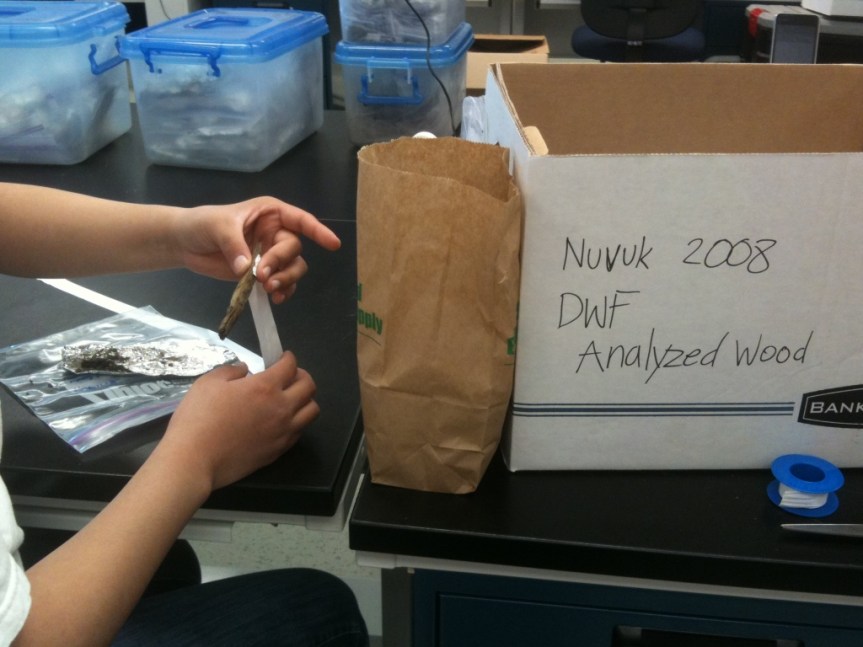

Now, however, it is becoming clear that museums cannot expand indefinitely, and that not everything can be kept. In fact, some places are deaccessioning items. Many places are being much more selective in what they will accept. There is a real storage space crunch in Barrow (particularly for climate controlled storage) so we need to be judicious about what is retained for the future.

At the same time, we are excavating with crews which include beginning excavators, in sometimes unpleasant weather. The only good way to make sure that important data (or artifacts) don’t get left in the field is to have people collect things even if they are not sure they are artifacts. And they do.

When the bags are gone through and the contents cleaned, obvious mistakes are discarded at that point. That still leaves an enormous volume of material. There simply isn’t place for it all, so some decisions have to be made in how to deal with it. The most rational approach is to discard the items with the least information potential first.

The Point Barrow spit has been used by people and animals for the entire period of its existence. Faunal remains have been dropped and scattered by humans and animals alike. Artifacts have been dropped and lost and refuse has been tossed. That’s true of most sites, but the post-depositional processes acting at Nuvuk are a bit different.

At the majority of sites, the site is built up like making a layer cake. The bottom layer goes on the plate first, then a layer of frosting, then another layer of cake, and so forth. The oldest layer is on the bottom, and the newest on top. If you put a piece of candy on the cake and push it down into the bottom layer, there are traces of that, so that it is possible to figure out that it was the last thing added.

At Nuvuk, on the other hand, the loose gravel matrix means that something can be dropped on the surface, stepped on twice and be 10 cm under the surface, covered with apparently undisturbed gravel, in 15 minutes. Digging can bring older items to the surface, as can frost heaving and the action of tires. In other words, there is no way to tell what was deposited before what. One can get relative dates for artifacts based on their style or even patent dates for trade items, but that doesn’t tell you anything about when they were deposited at the site. Faunal remains are even worse. There is no way to date them (C14 dates at $900/bone aren’t likely to happen) and since polar bears hunt the same animals as the Nuvukmuit (people of Nuvuk) did, and drop bones on site, we can’t even be sure the bones were introduced by humans. The only exceptions are areas where there was a sufficient amount of organic matter to support plant growth and soil development. These include the graves and middens (and the sod houses before they eroded away).

This difference was taken into account when we developed the protocols for shovel test pits. The excavators collected the artifacts and faunal material by natural levels. In most cases, the entire STP was in the same loose gravel level. This means that the materials from those STPs have much less information potential that the materials from the areas of the site with some soil development and stratigraphy. Any research questions that could be addressed with this material can also be addressed with material with better stratigraphic control, at far less cost and with more confidence in the results. That makes them an ideal place to start when trying to reduce the volume of the collections to be retained for the long-term.

We have been digging over 2000 STPs each season (and really hope the GPR will reduce that a lot). Some of them had nothing in them, but most had at least a few animal bones and artifacts. So we are working with the bags from STPs where there had been only an undifferentiated gravel level. Any particularly interesting or unique artifacts are being saved (although they are few and far between, most having been found during excavation). Recent trash (cigarette butts, juice boxes, etc), recent nails & metals straps, cloth gloves and the like are recorded and lab discarded. Items with maker’s marks or other markings that might allow identification and/or dating are being retained for further analysis, and others are being sorted, counted and recorded prior to lab discard. So far there seems to be a good collection of Pabst Blue Ribbon cans from the pull-tab era. We are also retaining items (gears, lock sets, etc) which look as if they might be further identified with the right documentation for additional analysis. The faunal material is being sorted. Modified items are being retained for further analysis, identifiable elements are being recorded and lab discarded (with particularly good examples being saved for a teaching collection), and unidentifiable fragments are being counted and lab discarded. This is good practice for the students, and since the STP material isn’t well-suited for future research (due to the issues mentioned above), overall this is a positive step.