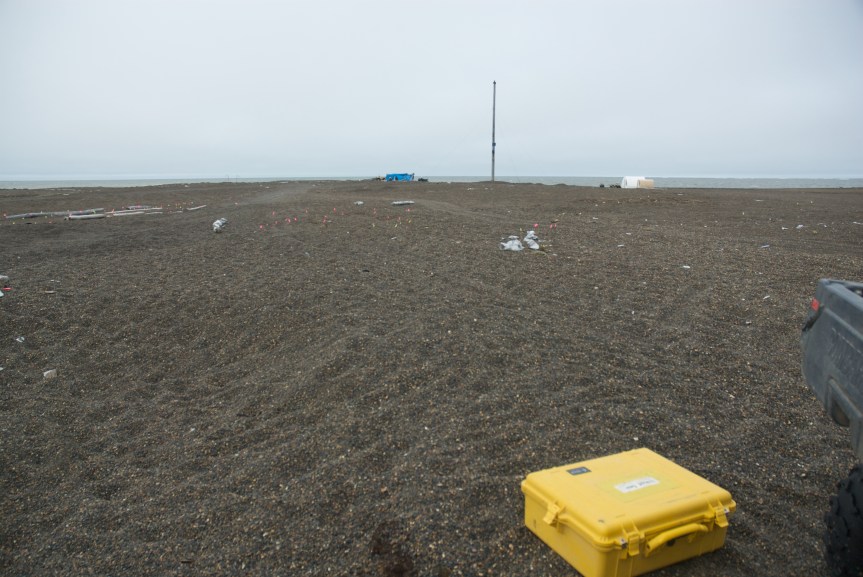

I mentioned that we started excavating a burial on the 15th of July and didn’t finish until the evening of the 19th, due to some really nasty weather. It was simply too windy to excavate from Thursday afternoon until Monday the 19th after lunch. Rain, sleet, and snow are all bothersome, but can be worked around. Once the wind speeds get over about 30 mph, the chances of small artifacts (or even worse, small skeletal elements) being moved before their position is recorded or even blowing away altogether is real. Wind speeds at Nuvuk are usually 5-10 mph higher than the official NWS measurements in Barrow. Last year we had a Kestrel 4000 portable anemometer on site, but Laura’s dog Sir John Franklin ate it, so we have to estimate a bit.

We started work on the burial, called 10A927 on Wednesday, clearing vegetation and the organic soils covering the actual burial. On the 15th, we began exposing the individual. The skeleton was quite well-preserved. It quickly became apparent from the size of the femur (thighbone) that this had been a very large person. Dennis O’Rourke, the physical anthropologist who has the grant to work on the aDNA from Nuvuk, helps with the excavations each season. He’s pretty tall (I’m guessing maybe 6’4″) and his opinion was that the burial was of someone who was very close to his height. That would pretty much have been a giant at the time of European contact, since the tallest man the Ray expedition’s surgeon George Oldmixon measured in 1882-3 was 5’8 3/4″ tall. There have been several other fairly tall individuals in the ancient graves at Nuvuk, so maybe the average height was depressed at contact because of poor nutrition because Yankee whaling had depleted the whale stocks pretty badly. We were able to get an aDNA sample, which we take as soon as the ribs begin to show. Jenny suits up and excavates and collects a previously unexposed rib. Weather forced us to tarp the burial to protect it until conditions improved.

On Monday the 19th, the weather was pretty bad in the morning, but by lunch time it was improving, so we went out. The passing of the storm had brought the winds around from SW to ENE, so the first order of business was to move the windbreaks on burials 10A927 and 10D75 (which we were excavating simultaneously). We then began excavating. 10A927 turned out to be a very interesting burial. The skeleton was nearly complete and well-preserved, and the positioning and grave structure were pretty typical for Nuvuk. It was very nice to be able to show the students a real-life example.

I can’t show any pictures, as the Barrow Elders do not want them made public, based on past unfortunate experience. I’ll do my best to describe the burial. A shallow pit had been dug in the gravel (it’s pretty hard to dig anything else, even with metal shovels, which they didn’t have back then), and surrounded it with a “frame” of wood and/or whalebone. 10A927 had a nice whale rib at the foot, and wood at the sides and head. The man had been placed on a hide, probably caribou, on his back with his knees bent. His legs were bent a bit more than usual for Nuvuk, with his feet right by nis pelvis, almost as if the grave had been a bit small. Perhaps the grave diggers had made the standard grave and he was a little too tall to fit easily. His face was turned left. His arms were folded over his chest and stomach.

A number of things had been put in the grave with him. We found a number of whalebone bola weights (bolas were used for hunting birds), which may actually have been put in as a complete bola. We also found a lot of the beach cobbles (bigger than the regular gravel and not that common at Nuvuk) that we have come to call “burial rocks” that were placed in some burials. Most interestingly, he had the top of a human skull , which had apparently been placed on his stomach under his hand, since we found finger bones and a bola weight in it. The skull appeared to have been on the surface at one point, as it was lighted in color than the skeleton, but it seems to have been placed in the burial deliberately, not found its way in later. We have had a couple of burials with more than one person in them, and some where a later burial had disturbed an earlier one and ended up with parts of the earlier burial in and around the later one, but nothing like this.

All this was quite complicated to excavate and record. Since the high school students are all minors, and some are only 15, the easiest way to avoid violating any child labor laws is to make sure they don’t work late. So they went back to town with one of the bear guards just before 5pm, and the rest of us (Jenny, Laura, Ron & I) stayed out to finish. It’s kind of unfortunate, since we only work late when something delicate and usually interesting is being excavated, and it seems tough on the students to make them leave just as things get really cool, but since this is a real job for them, we have to be on the safe side and follow all the rules.

We didn’t get done until about 9:15pm. It wasn’t the greatest weather for all this (never got above 36ºF) but at least the wind dropped for the last couple of hours.