Shawn made it in on Friday, but some of his digitizing equipment, which had been shipped in advance with a promise from UPS that it would be here last Tuesday or Wednesday, didn’t. He had to start with analyses that didn’t need the equipment, and we’re hoping it gets here in time for him to use it before he travels back to Utah on Wednesday.

Here’s hoping the plane makes it in tonight…

…because Shawn Miller, the physical anthropologist who will be documenting the human remains excavated at Nuvuk this summer, is supposed to be on it. The weather has been rather unfortunate of late, and a number of flights have tried to land, only to be turned back by visibility below minimums, thanks to the fact that the folks who sited the Will Rogers-Wiley Post Memorial Airport seem to have picked the foggiest spot they could find. A lot of folks have gone back and forth between Anchorage or Fairbanks and Barrow a couple of times by now (and you don’t get frequent flier miles for that).

We’ve got the lab all ready, and Laura is getting Shawn’s equipment (various digital measuring devices) out in case he wants to get an early start. Once he’s done, we can arrange the reburial.

RIP Uncle Ted

“Where there was nothing but tundra and forest, today there are now airports, roads, ports, water and sewer systems, hospitals, clinics, communications networks, research labs and much, much more.” (from Senator Theodore F. “Ted” Stevens’ final speech in the United States Senate).

I read those words yesterday. When I did, I was sitting in my office in one of those research labs, the Barrow Arctic Research Center (BARC). Down the hall is the beautiful lab occupied by the Nuvuk Archaeology Project. Like so many other things in Alaska, especially rural Alaska, it wouldn’t be there if it weren’t for Uncle Ted.

When the building was done, there was a Grand Opening, to which the entire Alaska Congressional Delegation was invited. We were asked to move from our old lab in another building to the BARC, so that some research would be happening there when the opening happened. There was a nice ribbon cutting ceremony, and then the dignitaries toured the building.They visited the lab, and Uncle Ted really looked at the materials we had laid out, asked questions, and was great about taking time to talk with high school students.

He was particularly fascinated by some Yankee whaling gear that we had recovered from the work area that had been used by an umialik (whaling captain) and his crew. When he (and Representative Don Young–the only one Alaska has) posed for pictures with the students, he wanted to hold one of those artifacts, a Yankee whaling iron.

Ted Stevens was a gentleman and a truly great man. He spent his adult life in public service, for Alaska and his country. He was a genuine war hero, with a Distinguished Flying Cross to his credit, flying transports in the China-Burma-India theater during WWII. He graduated Harvard Law, worked as a federal prosecutor in Fairbanks, served at Department of the Interior in the run-up to statehood, practiced law and was first appointed to fill the seat of the late Senator Bob Bartlett in 1968. He won election to that seat, and served Alaska in the US Senate for 40 years.

There, he had a huge influence on the state of Alaska, and the US as well. Ted Stevens was a major factor in shaping the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) which more-or-less settled the thorny issue of Native land claims, established the regional and village Native Corporations, and made construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline possible. He got the TAP through the Senate, and that made Prudhoe Bay development possible. Prudhoe Bay supports about 90%± of the State of Alaska budget, so this would be a very different place had that not happened. He was influential in drafting the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), which set aside a considerable amount of federal land in Alaska (not so popular in Alaska; it cost Mike Gravel his Senate seat) and protected Native subsistence rights. He co-authored a fisheries act that made the Alaska fisheries the best-managed in the US, and among the three best in the world, improved fishing safety (the Deadliest Catch isn’t anymore), and figured out a way to get some of the money being made on those fisheries to the impoverished original residents of the region. The Denali Commission, which he established based on the example of the Appalachian Commission, has brought money to the state to help poor rural communities raise their standard of living to something a bit closer to what most Americans simply take for granted as their birthright. He worked incredibly hard to improve aviation safety, not only in Alaska, but throughout the US. He kept the USPS from degrading service to rural Alaska, and pushed the bypass mail system, which kept mailing costs (and the cost of living in rural Alaska) down a bit, and insured some revenue to passenger carriers, keeping routes to small rural communities which can only be reached by air commercially viable.

People in Alaska know that he fought for them tirelessly, and almost to a person can cite something he did that made their lives better. He wasn’t about power for power’s sake, or for personal aggrandizement. He knew that power & seniority were tools so he could do a better job for Alaskans.

I’ve noticed that some non-Alaskans don’t get it. They just see Ted Stevens as a pork-barrel politician. They are wrong. He did indeed bring money to Alaska. That was his job. It was also the right thing to do.

For a good century, fortunes in gold, whale oil and baleen, furs and fish have been hauled out of Alaska to places like Seattle and San Francisco, leaving precious little benefit to the people of Alaska. With the exception of Hawaii, the other states of the union have benefited from a century or more of federal largess, either in the form of direct federal investment like highways, locks and dams, or by way of indirect subsidies like tax breaks or free land for railroads, homesteaders and so forth. When Stevens took office, the state of sanitation and public health in many rural villages might have been the envy of peasants in rural India, but not of most other people. Conditions were worse than most Americans can even imagine. People were poor, had little opportunity for Western education, in many cases were far more fluent in their Native language than in English, and had been pushed into moving into houses that were impossible to heat without expensive fuels that required cash to buy in communities where there was no wage labor. A lot of people would have just ignored these folks, because there aren’t very many of them, and they were not politically sophisticated. Ted Stevens didn’t. He did the principled thing.

When Ted Stevens tied on the Incredible Hulk tie and headed for the Senate floor, he was fighting for what was right, as he understood it. He didn’t just think of Alaska, either. He fought very hard for funding for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and National Public Radio (NPR), even when that was not a position popular with the Republican party. He was also instrumental in restructuring the US Olympic movement to bring central control to the USOC. He was a proponent of Title IX, which has been of so much benefit to so many female athletes throughout the US. He was willing to work with those on both sides of the aisle, in order to get things done to benefit his state and his country, and he was very effective at it.

Along the way, he survived a plane crash that killed his first wife, and all but one other person on the Learjet. Unfortunately, he didn’t survive this one. Alaska and indeed the world, is a poorer place for it. May he, and the others who perished with him, rest in peace.

Meanwhile…

While the dental extern was busy in the lab, Laura was there to help her find things, answer questions, and so forth. I was busy with other things.

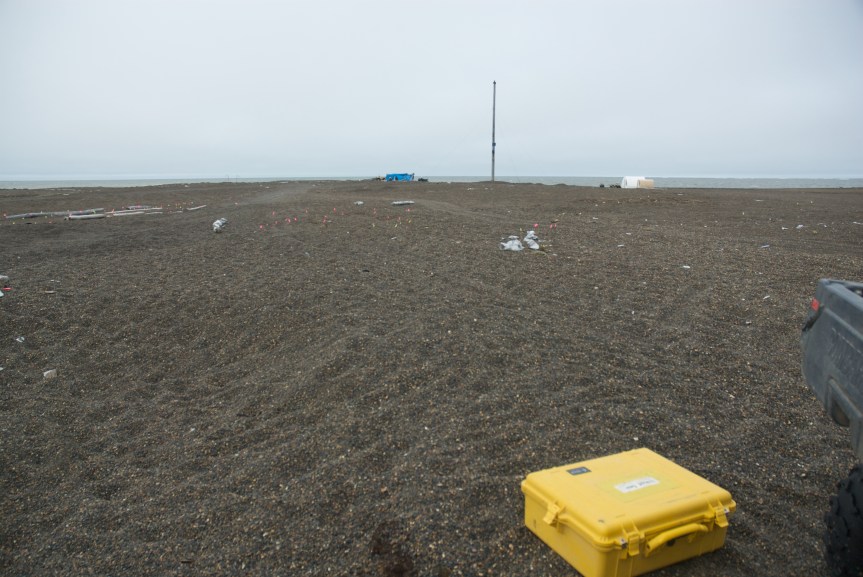

A couple of Navy archaeologists (yes, the US Navy has archaeologists) were in Barrow last week to look at a tract that the Navy may be transferring to UIC, the Barrow village corporation, to get an idea of what needs to be done to comply with cultural resource protection laws prior to transferring Federal land. Neither of them has any Arctic experience, and they stopped by my office to pick my brain a bit. The next day they were doing a few STPs on an old beach ridge on the tract, and asked if I’d like to join them. It was a warm sunny day, with not much wind, and therefore many mosquitos. I hiked our from my office building to meet them, we checked out the area a bit & I hiked back. Other than all the bugs, it was great.

We didn’t find anything cultural that was older than NARL, but we did find a couple very old gravel beaches. We did find some stakes that had probably marked research plots, and a big aluminum object that looked like an aircraft part. It had some cable attached to the front, as if someone had been trying to tow it. Apparently they gave up. If you happen to recognize this, please let me know and I’ll pass the information on.

The next day I got a call from the City of Barrow. They run the cemeteries, and had been getting reports that a coffin was partially open. They had checked, and indeed a coffin had been frost-heaved and was damaged. They asked if I could come over when they moved the person into a new coffin. We decided to do it the next afternoon, after they got the new coffin built.

Fortunately, the old coffin wasn’t damaged except for a bit of the lid, so we were able to get the dirt off to make it lighter without disturbing the remains. The City crew was able to lift the entire box out and place it in the new larger coffin. It was a tight fit, because the old coffin had been covered with canvas that was nailed on, but that wasn’t clear when they had measured for the new box! Luckily they had left a bit of space, so they were able to pry a bit and get it in. I got the canvas that had frozen in out so it could go along. I’d mostly been there in case the coffin was fragile and we had to transfer the individual, to make sure that nothing got left, but that wasn’t needed.

Once the coffin was out of the grave, the idea was to dig it a bit deeper, and then rebury the person. The soil profile was pretty interesting. There was clay (which generally is deposited on the bottom of bodies of still water) very close to the surface, despite the fact that the grave was on a mound. Apparently the permafrost has pushed it up a good bit, although it may have been deposited when sea level was higher than today.

The crew did what they could with shovels, but thaw was not that deep, as you can see from the picture above, so they were going to get a compressor and jack hammer, to really get the grave deeper, when I left. If not, frost heaving would just bring the box up again in a few years.

The deceased see a dentist

This week, the individuals we excavated this summer saw a dentist. This is not as silly as it may sound.

The various individuals whose burials we excavate at Nuvuk are not kept in a museum somewhere for future study. That is the way things were done in the past, but nowadays that is not acceptable to most descendant communities (people who consider themselves descended from the individuals whose remains are in question). There are laws specifically to protect Native American graves, as well as laws which protect all graves regardless of the ethnic origin of the occupant. This is a good thing, but it does mean that either research has to be completed very quickly, or new ways to save data for future research need to be found.

The current residents of Barrow, some of whom are the children of people who grew up at Nuvuk, generally think people should be left where they were buried, absent a pressing reason to move them. In general, I agree. My primary research interests don’t involve digging up burials, which makes it odd that I’ve been involved in excavating over 70 of them at Nuvuk over the years. The thing is, the point is eroding, and if the graves aren’t excavated and moved, their occupants will wind up in the ocean. So there is an urgent reason to be doing these excavations.

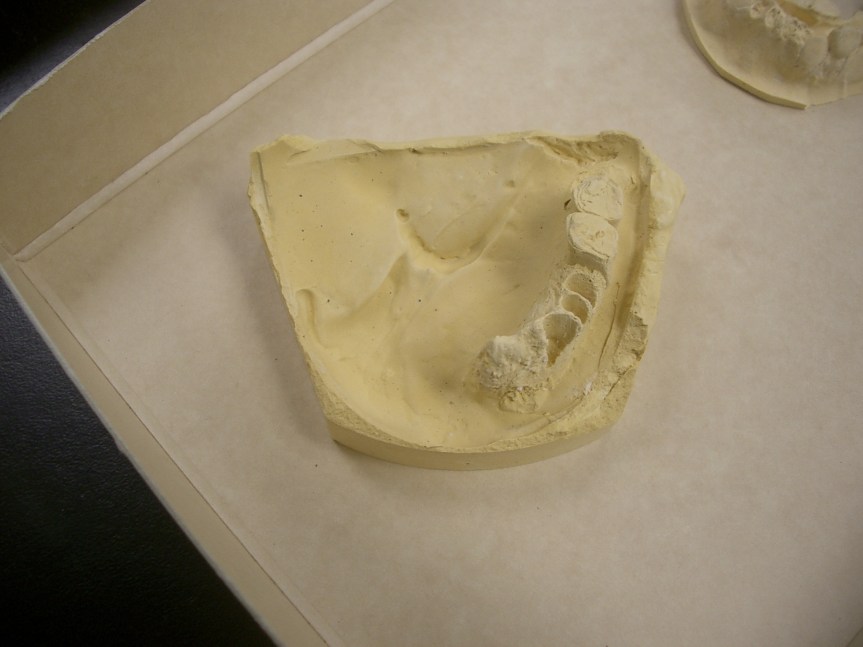

Since they are happening, most folks in Barrow agree that it makes sense to learn as much as we can about the individuals, prior to reburying them in the Barrow cemetery. I’ve mentioned that a rib is saved for aDNA extraction, which takes place in Dennis O’Rourke’s lab at the University of Utah. Everything else happens in Barrow. For a number of years, the Dental Clinic at Samuel Simmonds Memorial Hospital has sent one or more dental externs (dental students who have come to Barrow to get practical experience in the clinic) to work with the Nuvuk Archaeology Project for a day or two at a time. Sometimes they have come to the field with us, but their primary role has been in the lab, where they examined the teeth of the various individuals whose remains we have recovered. In addition to recording the teeth on standard dental charts, including information on disease and anomalies, they have made casts of the teeth, just like the ones dentists make of live patients in their offices. The idea came Amanda Gaynor-Ashley, DDS, until recently head of the dental clinic, who was visiting the lab a few years ago and noticed that some of the skulls had unusual dental patterns that looked just like those she was seeing on patients in the chairs at the clinic. Dentition (shape and arrangement of the teeth) is highly heritable (it runs in families). Since the individuals we were looking at were going to be reburied, Mandy suggested trying to cast their teeth. It worked well, and each since the externs have done it for the individuals excavated that year. Even after they are buried, we will have an accurate representation of their teeth for future researchers.

Since we started doing this, I stumbled across a mention of a collection of dental casts of living Barrow residents which was made by a researcher in the 1950s. It apparently still exists, so the casts we are making as part of the NAP may well have an important place in a future research project.

Later this week, Shawn Miller, the physical anthropologist from the University of Utah will arrive. We will have to get the casts put away before that to give him maximum space to work.

Moving the datum

Since 2004, we have had a primary site datum NUVUK 1, with two others that were used as control points. As the bluff continued to erode, it became clear that we would need to abandon the primary datum, so last year local surveyor Chris Stein set three more datums. This year, the primary datum was no longer a good place to set up, so I switched to setting the total station up at NUVUK 2 (our former primary reference point, and using NUVUK 1 as the reference.

The program we use, called EDM, is a really nice special purpose piece of software, written just for recording archaeological excavations with a total station. It is really configurable and can make major use of menus, which means no typos and a cleaner field catalog down the road. It allows you to set up (once you get the instrument over the datum point and level) by putting a reflector on the reference point (another datum for which you have coordinates, telling the program where the instrument is. It then does the geometry and lets you confirm where the program thinks the instrument is and which way it is facing. With that information and the angle and distance to any other point, the program does the geometry to figure out where the artifact you are recording is in the site grid.

For all this to work, the datums have to be precisely recorded. On July 20th, we actually had to move NUVUK 1. When Chris set it, he’d chosen a high point, with vegetation, as a good stable vantage point. The only problem was that we weren’t sure that it didn’t have a grave under, and the erosion was getting closer. We had to pull it and see, rather than risk loosing a person to the ocean. All the other datums were quite far away (a good thing for control points) so we needed something more convenient to where we were excavating for ease in checking the setup, or restarting after battery issues. I picked a spot below one of the guy wires for the beacon pole, since the wire made it less likely that anyone would disturb it with a vehicle. We made extra sure of our setup, checked it with NUVUK 4, and tried to yank NUVUK 1.

It didn’t want to come out. We tried tapping gently with a mallet. We really didn’t want to be too aggressive, because we weren’t sure if it was in a burial. In the end, we had to excavate shovel test pits all around to loosen it enough to remove. Fortunately, there was no burial.

We put the stake into the chosen new location, and shot it in. For the rest of the season, we checked setups with NUVUK 4 as well as NUVUK 1(A), and it seems to be stable.

While all this was going on, part of the crew was finishing excavation of another burial 10D75. This burial appeared to be quite disturbed at first, but actually was fairly well-preserved except for the top. The rest of the crew was STPing. Rochelle found one burial in an STP, and Trace found another by exposing some aged wood (we call it “burial wood” because the wood in burials just has a certain look to it) while walking. We recorded and back-filled STPs around the two locations so that we could shift windbreaks there the next day.

The burial of a very large man

I mentioned that we started excavating a burial on the 15th of July and didn’t finish until the evening of the 19th, due to some really nasty weather. It was simply too windy to excavate from Thursday afternoon until Monday the 19th after lunch. Rain, sleet, and snow are all bothersome, but can be worked around. Once the wind speeds get over about 30 mph, the chances of small artifacts (or even worse, small skeletal elements) being moved before their position is recorded or even blowing away altogether is real. Wind speeds at Nuvuk are usually 5-10 mph higher than the official NWS measurements in Barrow. Last year we had a Kestrel 4000 portable anemometer on site, but Laura’s dog Sir John Franklin ate it, so we have to estimate a bit.

We started work on the burial, called 10A927 on Wednesday, clearing vegetation and the organic soils covering the actual burial. On the 15th, we began exposing the individual. The skeleton was quite well-preserved. It quickly became apparent from the size of the femur (thighbone) that this had been a very large person. Dennis O’Rourke, the physical anthropologist who has the grant to work on the aDNA from Nuvuk, helps with the excavations each season. He’s pretty tall (I’m guessing maybe 6’4″) and his opinion was that the burial was of someone who was very close to his height. That would pretty much have been a giant at the time of European contact, since the tallest man the Ray expedition’s surgeon George Oldmixon measured in 1882-3 was 5’8 3/4″ tall. There have been several other fairly tall individuals in the ancient graves at Nuvuk, so maybe the average height was depressed at contact because of poor nutrition because Yankee whaling had depleted the whale stocks pretty badly. We were able to get an aDNA sample, which we take as soon as the ribs begin to show. Jenny suits up and excavates and collects a previously unexposed rib. Weather forced us to tarp the burial to protect it until conditions improved.

On Monday the 19th, the weather was pretty bad in the morning, but by lunch time it was improving, so we went out. The passing of the storm had brought the winds around from SW to ENE, so the first order of business was to move the windbreaks on burials 10A927 and 10D75 (which we were excavating simultaneously). We then began excavating. 10A927 turned out to be a very interesting burial. The skeleton was nearly complete and well-preserved, and the positioning and grave structure were pretty typical for Nuvuk. It was very nice to be able to show the students a real-life example.

I can’t show any pictures, as the Barrow Elders do not want them made public, based on past unfortunate experience. I’ll do my best to describe the burial. A shallow pit had been dug in the gravel (it’s pretty hard to dig anything else, even with metal shovels, which they didn’t have back then), and surrounded it with a “frame” of wood and/or whalebone. 10A927 had a nice whale rib at the foot, and wood at the sides and head. The man had been placed on a hide, probably caribou, on his back with his knees bent. His legs were bent a bit more than usual for Nuvuk, with his feet right by nis pelvis, almost as if the grave had been a bit small. Perhaps the grave diggers had made the standard grave and he was a little too tall to fit easily. His face was turned left. His arms were folded over his chest and stomach.

A number of things had been put in the grave with him. We found a number of whalebone bola weights (bolas were used for hunting birds), which may actually have been put in as a complete bola. We also found a lot of the beach cobbles (bigger than the regular gravel and not that common at Nuvuk) that we have come to call “burial rocks” that were placed in some burials. Most interestingly, he had the top of a human skull , which had apparently been placed on his stomach under his hand, since we found finger bones and a bola weight in it. The skull appeared to have been on the surface at one point, as it was lighted in color than the skeleton, but it seems to have been placed in the burial deliberately, not found its way in later. We have had a couple of burials with more than one person in them, and some where a later burial had disturbed an earlier one and ended up with parts of the earlier burial in and around the later one, but nothing like this.

All this was quite complicated to excavate and record. Since the high school students are all minors, and some are only 15, the easiest way to avoid violating any child labor laws is to make sure they don’t work late. So they went back to town with one of the bear guards just before 5pm, and the rest of us (Jenny, Laura, Ron & I) stayed out to finish. It’s kind of unfortunate, since we only work late when something delicate and usually interesting is being excavated, and it seems tough on the students to make them leave just as things get really cool, but since this is a real job for them, we have to be on the safe side and follow all the rules.

We didn’t get done until about 9:15pm. It wasn’t the greatest weather for all this (never got above 36ºF) but at least the wind dropped for the last couple of hours.

“Today it’s like heaven!”

Yesterday the weather was very nice, our first real summer day, just in time for a site visit by a number of Barrow Elders with family ties to Nuvuk. A fine time was had by all.

Today the weather started out even better, if possible. It was sunny, with blue sky and blue ocean, and so little wind that we actually had mosquitos. We finished one of the two burials we were working on around lunch, just as it started to cloud up. The other burial was done around 3 pm, and we started shooting in and backfilling STPs. Both burials were quite interesting,and both had harpoon heads as grave goods, which we haven’t had since the first burial.

Laura and the students went in early, since there really wasn’t enough for everyone to do, and Laura had to catch a plane to California for her sister-in-law’s wedding this weekend. Dennis, Jenny, Ron, Richard the bear guard and I stayed out to finish. We had a slight delay due to transit battery issues, and a dry fine mist rolled in. We managed to shoot in everything, including some delicate surface artifacts from portions of the site we haven’t reached yet, which are being collected to avoid damage from traffic. Ron and Richard even backfilled a lot of the remaining STPs! The students are very lucky…

Tomorrow we’ll have part of the crew in the lab, and the rest will go out to finish backfilling and haul gear back to the road, where they will meet Jenny in the project truck, who will haul the gear back to the lab for cleaning and storage. It’s very satisfying (and quite a relief) to actually have accomplished what I wanted & have all the data collected a day AHEAD!!

We can break equipment too!

One of my colleagues, Matthew Betts, who has done Arctic work for years, is currently excavating a large shell midden at Port Joli, Nova Scotia. He also has a project blog, and in a recent post on trowels, there was news of the sad demise of a Marshalltown trowel. Marshalltowns are great trowels, and I’ve never seen one break the way this one did. They usually wind up being discarded after being resharpened so many times they are nubs.

However, in the spirit of friendly competition (?) I’d like to point out that we have broken a larger piece of excavation equipment this season; to whit, a Sear Craftsman shovel (the yellow-handled kind). The evidence is below:

To be fair, I’ve seen these things break before, but it involved heavy equipment. We’re not sure what happened with this one. These are great shovels (maybe only archaeologists and landscapers can get so enthusiastic about shovels), but have to be special ordered to Barrow, which is sometimes a very convoluted process. That is why it has the pink and green duct tape rings on the handle. That way, we can recognize our shovels when they get “borrowed” and borrow them back.