I promised to put up a few pictures, so here they are:

And for the piece de resistance:

Pretty cool. And you should see all the micoflakes the students managed to get out of the matrix in the lab! Truly heroic effort on their parts.

I promised to put up a few pictures, so here they are:

And for the piece de resistance:

Pretty cool. And you should see all the micoflakes the students managed to get out of the matrix in the lab! Truly heroic effort on their parts.

Much of today went trying to find freezer space for the person in the parka. We were able to get X-rays done by the North Slope Borough vet clinic (they needed a bit of practice with a new machine anyway), and there are skeletal elements in the parka. I talked to a conservator and it seems possible that the garments might be able to be preserved if the community chooses. We need to have a discussion with the Elders about that.

At least we need to document them really well, as they are being removed so the person can be examined and reburied. To do that we need not only a good videographer, but also a group of experience skin sewers, since the sinew has decayed, and it may only be possible to figure out what stitch was use by skilled sewers looking at the ghosts they left. We need to get the funds for that work, which probably won’t be available until October or so. That means that we need a freezer to keep the person in a stable environment until the examination can happen.

CPS/UMIAQ couldn’t really offer anything right now, except to note that it hadn’t been requested in the program plan last year (sadly, I’m not clairvoyant–if I were, we could skip all the pesky shovel testing). Fortunately, North Slope Borough Wildlife Management also has a freezer, and they were kind enough to step up and help out in this urgent situation. Many thanks to DWM! One UMIAQ fellow later thought of a freezer that might be a possible fallback, although it’s got stuff in it at the moment.

Next step, grant applications for that work and for the Ipiutak structure that remains at the bluff in the DWF, waiting for the next big storm to take it out.

The weather was not pleasant. It rained all day, and was pretty cold. My fingers are swollen up like sausages. The rain also took out the track pad on the computer for the transit, so we couldn’t back up the files in the field. We were able to use a mouse in the lab, and got the files backed up and transferred to the other laptop, so if the track pad doesn’t perk up, we’re OK. My Nikon Coolpix S9100, which I just got last night to replace one that failed after a week, died the same way today. Nikon won’t issue a refund for 15 days, which is truly ridiculous under the circumstances. I’ve been committed to Nikon, loved all the SLRs I’ve had (FM, 4 FEs, 4 N70s, D200) and liked everything about this camera, too, except it won’t work. Epic fail. So don’t buy one!

On the plus side, the very deep burial turned out to be a person wearing a fur parka and wrapped in hide! You can even see traces of the stitching. We aren’t sure how well-preserved the person is (we found a few finger bones and a nail inside the cuff). We decided to take it out en bloc (complete) and take it back to the lab to excavate in controlled conditions so we can document the garment better, since it is very fragile. We had some plywood brought out and managed to slide it through the gravel under the entire burial and lift the whole thing. This required the digging of a very large hole, which we’ll now need to backfill. Many thanks to Brower Frantz and his crew for bringing out the plywood and transporting the individual back to the lab while we kept on in the field.

The DWF keeps yielding more artifacts, some of which are quite nice. We’re trying to get to a reasonable stopping point and figure out a way to protect the exposed feature in case we can get funds to work on it in September.

The mad rush toward the field continues. Laura Thomas is back, so it was possible to slip out to attend to things like a staff meeting during the day. A good thing, since there is only one full work day left in the week for us in Barrow. Tomorrow and Thursday are half-day holidays for Nalukataqs (celebrations of successful whaling seasons hosted by captains and crews) and the multi-day Fourth of July/NSB Founders’ Day holiday kicks off on Friday, so we get the afternoon off then too. Monday, July 4th, is a holiday too, and then fieldwork starts, a week from tomorrow!

All of the new NSF crew was here, so we had planned to do the candy eating exercise. Unfortunately, the two new ECHO crew members, who probably needed it the most, were not in today, but due to the holiday and the fact that the large conference room where we do the exercise is booked on Wednesday, we decided to forge ahead. We wound up splitting into groups by gender (the first time that has happened, I think) and it was interesting how that turned out. The HS students were all old hands, so they got to be the actors. The girls worked collaboratively on a very complicated “site” and had to stop because they ran out of candy. The guys each more or less did their own thing in parallel.

We did a safety briefing on various hazards that might be encountered in the field (chiefly ATVs, cold, sun, the propane stove, generator, polar bears, and strains & sprains). Then there was a quiz on skeletal elements, to be repeated on Wednesday in hopes that people will do better. Actually, everyone seems to know what the elements are, but how the names are spelled is a bit sketchier. Since I’m tired of having to do global replaces of “humorous” with “humerus” (upper arm bones not being particularly funny), I think this is time well spent. The afternoon finished with repacking the supplies which had been shipped up from Anchorage priority instead of buying local :-(. That will complicate the returning of the Tylenol PM that showed up instead of Tylenol. I’m not sure why the person doing the shopping thought that was appropriate for a job site first aid kit?! Especially when everyone drives to and from the site…

After the crew went home, I had to work up a proposal for some work to be done later this summer. I got it all done except for the prices for helicopter time. Once I get them, I plug them into the spreadsheet and send it off.

Now I’m working on a concept paper for what could be done with a large collection that is here in Barrow at the Inupiat Heritage Center. I have to finish that this week, as well as get a small survey done of a site on Point Barrow where some researchers want to set up a current radar. So, back to work…

The past couple of weeks have been really hectic. The local students have been working in the lab, and I’ve been dealing with logistics non-stop.

We’re at the point where we could go through the bags from the shovel test pits. In the early days of archaeology, only artifacts were collected, and sometimes only the unbroken ones, at that. The details of their provenience were often recorded in very broad term. As the discipline progressed, new methods kept developing, and it became clear that many of the things that had been discarded could have yielded information, had they only been collected. The pendulum swung toward keeping everything, including large volumes of samples, on the principle that someday methods would catch up, and then the information could be recovered. This is the same reason that practice moved toward only excavating part of a site, or even of a feature.

Now, however, it is becoming clear that museums cannot expand indefinitely, and that not everything can be kept. In fact, some places are deaccessioning items. Many places are being much more selective in what they will accept. There is a real storage space crunch in Barrow (particularly for climate controlled storage) so we need to be judicious about what is retained for the future.

At the same time, we are excavating with crews which include beginning excavators, in sometimes unpleasant weather. The only good way to make sure that important data (or artifacts) don’t get left in the field is to have people collect things even if they are not sure they are artifacts. And they do.

When the bags are gone through and the contents cleaned, obvious mistakes are discarded at that point. That still leaves an enormous volume of material. There simply isn’t place for it all, so some decisions have to be made in how to deal with it. The most rational approach is to discard the items with the least information potential first.

The Point Barrow spit has been used by people and animals for the entire period of its existence. Faunal remains have been dropped and scattered by humans and animals alike. Artifacts have been dropped and lost and refuse has been tossed. That’s true of most sites, but the post-depositional processes acting at Nuvuk are a bit different.

At the majority of sites, the site is built up like making a layer cake. The bottom layer goes on the plate first, then a layer of frosting, then another layer of cake, and so forth. The oldest layer is on the bottom, and the newest on top. If you put a piece of candy on the cake and push it down into the bottom layer, there are traces of that, so that it is possible to figure out that it was the last thing added.

At Nuvuk, on the other hand, the loose gravel matrix means that something can be dropped on the surface, stepped on twice and be 10 cm under the surface, covered with apparently undisturbed gravel, in 15 minutes. Digging can bring older items to the surface, as can frost heaving and the action of tires. In other words, there is no way to tell what was deposited before what. One can get relative dates for artifacts based on their style or even patent dates for trade items, but that doesn’t tell you anything about when they were deposited at the site. Faunal remains are even worse. There is no way to date them (C14 dates at $900/bone aren’t likely to happen) and since polar bears hunt the same animals as the Nuvukmuit (people of Nuvuk) did, and drop bones on site, we can’t even be sure the bones were introduced by humans. The only exceptions are areas where there was a sufficient amount of organic matter to support plant growth and soil development. These include the graves and middens (and the sod houses before they eroded away).

This difference was taken into account when we developed the protocols for shovel test pits. The excavators collected the artifacts and faunal material by natural levels. In most cases, the entire STP was in the same loose gravel level. This means that the materials from those STPs have much less information potential that the materials from the areas of the site with some soil development and stratigraphy. Any research questions that could be addressed with this material can also be addressed with material with better stratigraphic control, at far less cost and with more confidence in the results. That makes them an ideal place to start when trying to reduce the volume of the collections to be retained for the long-term.

We have been digging over 2000 STPs each season (and really hope the GPR will reduce that a lot). Some of them had nothing in them, but most had at least a few animal bones and artifacts. So we are working with the bags from STPs where there had been only an undifferentiated gravel level. Any particularly interesting or unique artifacts are being saved (although they are few and far between, most having been found during excavation). Recent trash (cigarette butts, juice boxes, etc), recent nails & metals straps, cloth gloves and the like are recorded and lab discarded. Items with maker’s marks or other markings that might allow identification and/or dating are being retained for further analysis, and others are being sorted, counted and recorded prior to lab discard. So far there seems to be a good collection of Pabst Blue Ribbon cans from the pull-tab era. We are also retaining items (gears, lock sets, etc) which look as if they might be further identified with the right documentation for additional analysis. The faunal material is being sorted. Modified items are being retained for further analysis, identifiable elements are being recorded and lab discarded (with particularly good examples being saved for a teaching collection), and unidentifiable fragments are being counted and lab discarded. This is good practice for the students, and since the STP material isn’t well-suited for future research (due to the issues mentioned above), overall this is a positive step.

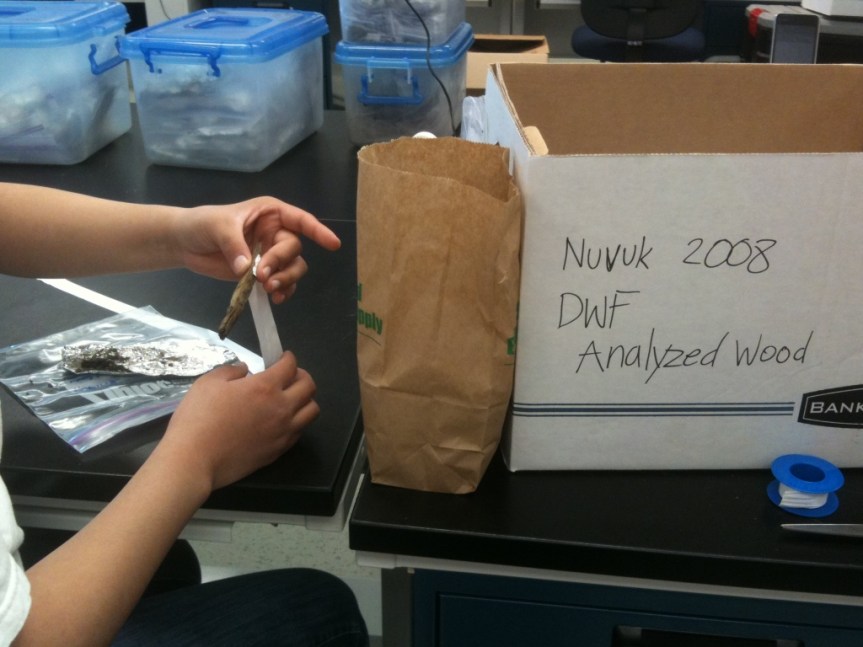

Claire Alix, who is probably the world expert on precontact wood use in Alaska, is in Barrow for a 10-day stint of analyzing wood from Nuvuk. She is working on wood from the Driftwood Feature (DWF), because there is so much of it and we need to figure out what needs to be kept.

The DWF was a storm strand line which was washed up onto and mixed with an Ipiutak settlement. Not just any Ipiutak settlement, but the farthest north Ipiutak settlement by about 500 km. The result was a mass of wood, bark and marine invertebrates, with a number of clearly identifiable artifacts included. There was so much wood that we called the level “Wood/Sand/Gravel” because it seemed like there was more wood than matrix. However, some of the smaller pieces of wood and bark were also worked, but it seems that the storm picked up smaller floatable artifacts and mixed them with driftwood. Given the field situation, it was impossible to examine each small piece of wood in detail, so we erred on the side of caution and brought back a lot of things that probably aren’t artifacts, so they could be examined in a nice warm lab.

The DWF was actually frozen, and had been for centuries, so we didn’t just want to bring the wood into a warm lab and let it thaw. That generally leads to wood that looked really well-preserved “exploding.” We have a nice walk-in refrigerator at the Barrow Arctic Research Center (BARC) just down the hall from my lab, so we have been holding the wood there, thawing slowly and keeping it cool to retard mold growth. The large and important artifacts started the conservation process very quickly, but there are boxes of smaller things which need to be inspected to separate the worked wood and bark from the rest. The wood that is just driftwood will be lab discarded, with that being recorded in the catalog so it will be clear in the future that artifacts haven’t been lost. The artifacts will get analyzed and better information will be recorded. This also lets us identify things for the conservator to work on when she next can come to Barrow. Small artifacts are being brought out for gradual drying. Wrapping wood in teflon tape to hold it together during slow drying has worked fairly well, so we’re doing that to move more out of the walk-in

All this is pretty laborious. Claire has to do the analysis and wood IDs, but with her schedule we needed to find a way to speed things up. The initial sorting of bags of wood and the wrapping of the wood are two of the most time-consuming aspects of the process. So, last week Heather Hopson came in to do some data entry and initial sorting, and this week Trina Brower is joining Heather. They are doing the initial sorts, wrapping with Teflon tape & data entry, so Claire can keep looking at wood.

Wrapping the delicate pieces of small wood is definitely fiddly work. It certainly helps having someone to work with & talk to while working.

And when all else fails….

I had lunch today with Monica Shah. She is one of two conservators (people with specialized training in the preservation of delicate and fragile items, like artifacts) in Alaska. She’s also a fellow Bryn Mawr alumna. Monica has been assisting and advising on the conservation of the wooden artifacts from the Ipiutak feature at Nuvuk, including the only two full-sized Ipiutak sled runners ever recovered. When we started, she was a free-lancer. She went to work for the Anchorage Museum, and they’ve been kind enough to let her continue working on the sled runners.

We went to a new restaurant on 4th Ave., called South. It has good sandwiches and generally HUGE portions. I can recommend the salmon salad, and Monica said the egg salad was tasty if rather sloppy. They have outside tables, but are a bit hampered by a tour company which picks up busloads of tourists right in front of them. Most of the tables were taken up by waiting tourists, most of whom weren’t buying anything. I hope they don’t get run out of business.

The Nuvuk artifacts are getting to the point in treatment where they need to come out of the PEG baths they’ve been in and get looked at by a professional. We figured out that Monica should be able to squeeze in a visit to Barrow in February. With any luck, we may be able to get good pictures of the sled runners in a few more months!

One of the things we collected a lot of from the strand lines was a variety of sea creatures. There are a lot of pieces of what we thought (in the field) was gut, which is a useful raw material. Now that we’ve gotten them into the lab, we think most of it is some sort of marine worms. There are also a variety of other small marine creatures (plants or invertebrates–they have lost their orignal colors) and mollusks.

Obviously, I know a lot more about mammal bones & teeth than these things. So we’ve sorted out a bunch, and Claire will take a couple of each type to Fairbanks, along with the shells. With any luck, we can get some IDs. If we’re really lucky, the species in question will turn out to have fairly narrow habitat requirements, and we’ll know something about what the ocean was like near Barrow when the big storm happened between 300 & 400 AD.

If you happen to recognize any of these, please let me know what you think they are. If you know anyone who might be interested in these creatures, send them my way. The “worms” are very well-preserved, and still flexible. It occurs to me that it might be possible to extract DNA from them (and maybe some of the other creatures as well), which would be a pretty rare opportunity.

The processing of the large bulk samples is proceeding. It’s slow going, but we are reducing the overall volume. We have found a few things that are noteworthy.

Claire has found some well-preserved wood that she was able to take samples of for species identification and possible tree-ring dating.

We also found one piece of coal with one flat, highly polished side. The rest of it looks like it broke naturally and got smoothed by being rolled in the water, but the one side looks different. It’s a maybe, but a pretty good one, although we’ll probably never know what it was or was going to be…

There are also a variety of marine worms, shells and what we think are marine plants. I just spoke to a friend of mine, “retired” biologist, Dr. Dave Norton, who used to live in Barrow and is fairly familiar with the contents of modern strand lines here. Claire is going to take the oddities we are sorting out down to Fairbanks (where he lives) tomorrow night, and he will look at the specimens and try to connect with the appropriate curators at the UAF Museum of the North. I’m going to Fairbanks (for shotgun refresher qualifications for a non-archaeology project I manage for Sandia National Labs) the week after next, and will go visiting the curators with him, in hopes of getting good IDs.