The second day in the field was devoted mostly to digging (shovel test pits). It was sort of chilly, and digging is a good way to keep warm. Besides, physical anthropologists Dennis O’Rourke and his post-doc Jenny Raff were due to arrive in Barrow that night (July 7). Since we are collecting small (a rib, generally) samples of the human remains for ancient DNA (aDNA) and stable isotopes and direct dating, and it is best if the samples are collected by one of the physical anthropologists, I decided to wait for them to join us in the field before beginning excavation of the burial we had located the day before.

We set out several more lines of STPs. STPs are common on archaeological surveys, where archaeologists are trying to find sites that may not be obvious when you just walk over them. Digging STPs makes it possible to see if there are artifacts or soil layers created by human activity buried in the ground. STPs are also used on known sites where one wants to find buried features (a term which can cover all sorts of concentrated physical evidence of past human activity–storage pits, hearths, houses, tent sites, turkey traps, reindeer corrals, places where someone sat to make a stone tool, you name it). Usually, they are a relatively minor part of work on a known site, serving mostly to choose where to dig. Often, they are placed on the site in a pattern which is either totally random (as in the locations are picked using a grid and random numbers) or what is called “stratified random” which means the site (or region–this works for survey too) has been divided into different areas (strata) based on something like slope or distance from water or vegetation cover, which each stratum being sampled separately. This avoids the possibility of not testing one stratum at all, which can happen with plain random sampling.

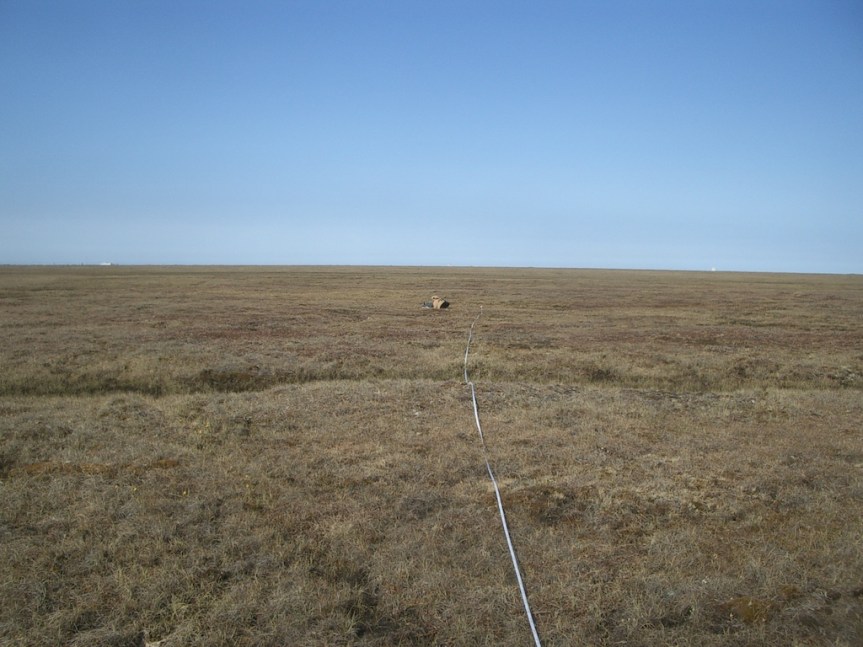

We are not doing random sampling of any sort. Nuvuk is, among other things, an area where people in the past buried their dead. Many of their descendants still live in or visit Barrow regularly. No one likes to think of their relatives, however distant, falling into the ocean due to the erosion of their final resting place. Random sampling is designed to help get a representative sample of whatever is in the ground, not to find all of it. We are trying to find everyone, and excavate them before erosion deposits them in the ocean. To do this we dig a lot of STPs. We had hoped to have some geophysical prospecting gear (GPS, magnetometer and resistivity) here this summer, and test them against the shovel testing in the Nuvuk gravels. If they worked, we’d have to shovel a lot less. Unfortunately, family illness prevented that happening this summer. So what we do is lay out a 50 m tape, place a pin flag every two meters (say on the odd numbers), drag it along and put out more flags and so forth, until we get a line across the entire ridge where the site it (it’s about 116 meter wide). Then we move the tape inland 2 meters, and do it over, except the pin flags would go on the odd numbers.

This spacing is close enough to pretty much guarantee that if there is a grave present some sign will show up in one of the STPs next to it, even if they don’t come right down on it. Actually, we prefer it if they don’t, but since most of the graves don’t show on the surface, it happens.

We have gotten far enough from the bluff that the trail to Plover Point actually crosses the area we are putting STPs in. When we lay out new lines, the first order of business is to dig and document all the STPs in the trail, record their locations with the transit, and backfill them (assuming there is no sign a grave might be there). We don’t want to obstruct the trail, since we’d like to keep traffic on it, rather than driving all over the site.

All the STPs bore fruit. We located three additional locations, two on the C line and one on the D line, that appear to be burials. There is plenty for us to do this field season already.